The Liberal Arts

Definition from Wikipedia:

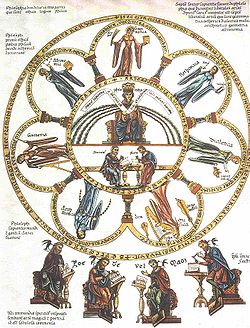

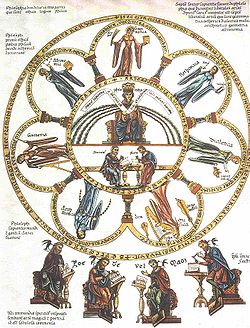

The seven liberal arts - Picture from the

Hortus deliciarum

of

Herrad von Landsberg

(12th century)

Liberal arts are the skills derived from the

Classical education

curriculum.

The term liberal arts denotes a curriculum that imparts general

knowledge and develops the student’s rational thought and intellectual

capabilities

unlike the

professional,

vocational, technical

curricula emphasizing specialization. The contemporary liberal arts

comprise studying

literature,

languages,

philosophy,

history,

mathematics,

and

science.[1]

In

classical antiquity,

the liberal arts denoted the education proper to a free man (Latin:

liber, “free”), unlike the education proper to a

slave. In

the 5th Century AD,

Martianus Capella

academically defined the seven Liberal Arts as: grammar, dialectic,

rhetoric, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and music. In the

medieval Western

university, the seven liberal arts were:

The Huffington Post

Michael Roth

President, Wesleyan University

December 1, 2008

Over

the next few months, in homes across America, seventeen and eighteen-year-olds

will be conferring with one another and with their parents about a life changing

decision: What college to go to! After months of research, visits, and advice

from "experts," these young men and women must now decide: Where will I be

happy? Where will I make friends? Where will I get an education I can afford

now, and an education that will remain valuable for years after graduation?

In

this same time period, our government officials will be deciding where an

investment in America's economic infrastructure will do the most good.

Commentators from different political perspectives have often noted that one of

the great advantages of America is its peerless higher education system.

Although other sectors have diminished international roles, higher education in

this country continues to inspire admiration around the globe. When politicians

talk about this, they often emphasize the research output of large universities,

but the focus should also be on American undergraduate liberal arts education.

Liberal arts in the USA provide not only a pipeline of talented and prepared

students to the great graduate schools, but also a model for life-long learning

that other countries are beginning to emulate.

But in

these challenging times, what's an education in the liberal arts good for?

Rather

than pursuing business, technical or vocational training, some students (and

their families) opt for a well-rounded learning experience. Liberal learning

introduces them to books and the music, the science and the philosophy that form

disciplined yet creative habits of mind that are not reducible to the

material circumstances of one's life (though they may depend on those

circumstances). There is a promise of freedom in the liberal arts education

offered by America's most distinctive, selective, and demanding institutions;

and it is no surprise that their graduates can be found disproportionately in

leadership positions in politics, culture and the economy. A quick look at

several members of President-elect Obama's leadership team can stand as an

example of how those with a liberal arts education are shaping the future of our

society.

What

does liberal learning have to do with the harsh realities that our graduates are

going to face after college? The development of the capacities for critical

inquiry associated with liberal learning can be enormously practical because

they become resources on which to draw for continual learning, for making

decisions in one's life, and for making a difference in the world. Given the

pace of technological and social change, it no longer makes sense to devote four

years of higher education entirely to specific skills. Being ready on DAY ONE,

may have sounded nice on the campaign trail, but being able to draw on one's

education over a lifetime is much more practical (and precious). Post secondary

education should help students to discover what they love to do, to get better

at it, and to develop the ability to continue learning so that they become

agents of change -- not victims of it.

A

successful liberal arts education develops the capacity for innovation and for

judgment. Those who can image how best to reconfigure existing resources and

project future results will be the shapers of our economy and culture. We seldom

get to have all the information we would like, but still we must act. The habits

of mind developed in a liberal arts context often result in combinations of

focus and flexibility that make for intelligent, and sometimes courageous risk

taking for critical assessment of those risks.

The

possibilities for free study, experimentation and risk taking need protection

and cultivation. Looking around the world, we find no shortage of thugs who

desecrate or murder those who seek to produce a more meaningful culture. And

here at home we can easily see how mindless indifference to the contemporary

arts and sciences facilitates the destruction of cultural memory and creative

potential.

America's great universities and colleges must continue to offer a rigorous and

innovative liberal arts education. A liberal education remains a resource years

after graduation because it helps us to address problems and potential in our

lives with passion, commitment and a sense of possibility. A liberal education

teaches freedom by example, through the experience of free research, thinking

and expression; and ideally, it inspires us to carry this example, this

experience of meaningful freedom, from campus to community.

The

American model of liberal arts education emphasizes freedom and experimentation

as tools for students to develop meaningful ways of working after graduation.

Many liberal arts students become innovators and productive risk takers,

translating liberal arts ideals into effective, productive work in the world.

That is what a liberal education is good for.

We

were surprised last week to hear reports from several liberal arts colleges and

universities that they had seen significant increases in 'early decision'

applications. At Wesleyan, we were up almost 40%, an increase none of us on the

staff would have predicted. Early decision applicants have already decided that

if they are accepted at the one school to which they apply in the fall, they

will attend that school the following year. Many of the highly selective schools

like Wesleyan have robust financial aid programs, accepting students regardless

of their ability to pay. In my next post, I'll write more about issues of

affordability even with financial aid.

In

these turbulent economic times, it appears that students want to know as quickly

as possible if they are going to be able to attend their first choice school.

Many of our talented high school seniors are doubtless deciding that the

significant investment of time and money in a liberal arts education will give

them the capacity for a sustainable and creative future. Perhaps they have

something to teach us!

C. S. Lewis on Liberal Arts Education

Gregory Dunn

On Principle,

v7n2

April 1999

When I received my Master of Arts

degree, as a gift I was given a T-shirt that read, "Liberal Arts Major: Will

Think for Food." The gift drew a smile then, and the phrase draws a smile now,

for it is a common sentiment that those who pursue what is called a "liberal

arts education" may have refined intellects but may also have difficulty paying

the bills once out of school. In truth, it is a widely held perception that such

an education is, at best, impractical and unnecessary and that it is preferable

to obtain a more useful degree, such as accounting, nursing, or engineering.

After all, with the time and expense of college education today, what use is it

to leave school without developing any marketable skills? In short, what good

are the liberal arts?

In answering this question, we will find

it helpful to look to C. S. Lewis for insight. Although best known in his roles

as imaginative writer, Christian apologist, and literary critic, we should not

forget that his profession was first an Oxford tutor and later a Cambridge

professor and that he spent the balance of his life--nearly forty years--in the

academy teaching literature. As such, Lewis wrote many incisive essays offering

a number of reasons why the pursuit of a liberal education is truly

indispensable.

To Preserve

Civilization

The first reason we study the liberal

arts has to do with freedom. That freedom is an integral part of the liberal

arts is borne out in Lewis’s observation that, "liberal comes of course

from the Latin, liber, and means free." Such an education makes one free,

according to Lewis, because it transforms the pupil from "an unregenerate little

bundle of appetites" into "the good man and the good citizen." We act most human

when we are reasonable, both in thought and deed. Animals, on the other hand,

act wholly out of appetite. When hungry, they eat; when tired, they rest. Man is

different. Rather than follow our appetites blindly we can be deliberate about

what we do and when we do it. The ability to rule ourselves frees us from the

tyranny of our appetites, and the liberal arts disciplines this self-rule. In

other words, this sort of education teaches us to be most fully human and,

thereby, to fulfill our human duties, both public and private.

Lewis contrasts liberal arts education

with what he calls "vocational training," the sort that prepares one for

employment. Such training, he writes, "aims at making not a good man but a good

banker, a good electrician, . . . or a good surgeon." Lewis does admit the

importance of such training--for we cannot do without bankers and electricians

and surgeons--but the danger, as he sees it, is the pursuit of training at the

expense of education. "If education is beaten by training, civilization dies,"

he writes, for "the lesson of history" is that "civilization is a rarity,

attained with difficulty and easily lost." It is the liberal arts, not

vocational training, that preserves civilization by producing reasonable men and

responsible citizens.

To Avoid the Errors

of Our Times

A second reason we study the liberal

arts is to avoid the prejudices of our age. "Every age," Lewis writes, "has its

own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable

to make certain mistakes." The way to avoid being ensnared by the popular errors

of our day, then, is to rub minds with the great men of the past, and the only

way to do that is to read books.

But they must be the right sort of

books. Lewis is adamant that a diet of contemporary books will not do the trick.

"All contemporary writers share to some extent the contemporary outlook," he

writes, and this outlook brings with it a "great mass of common assumptions"

that conceal a pervasive "characteristic blindness." Even those writers who seem

most opposed to each other will share this intellectual blind spot and will thus

make similar mistakes. "Where they are true they will give us truths which we

half knew already," Lewis writes. "Where they are false they will aggravate the

error with which we are already dangerously ill."

The only remedy is to cultivate a

discipline of carefully reading old books. His advice: "It is a good rule, after

reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read

an old one in between." In this way, we are able to identify and correct those

misperceptions that prevent our seeing the truth.

Lewis makes clear that the reason we

consult the minds of the past is not because they were perfect; in truth, they

were as subject to their own blind spots as we are to ours. The crucial

difference is that they did not have the same blind spots. Such writers

will not likely affirm the errors we now make. We will now not likely make the

same errors they did. As Lewis writes, "two heads are better than one, not

because either is infallible, but because they are unlikely to go wrong in the

same direction."

To Pursue Our

Vocation

A third reason we study the liberal arts

is because it is simply our nature and duty. Man has a natural thirst for

knowledge of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, and men and women of the

past have made great sacrifices to pursue it in spite of the fact that, as Lewis

puts it, "human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice." In his

words, "they propound mathematical theorems in beleaguered cities, conduct

metaphysical arguments in condemned cells, make jokes on scaffolds." So, finding

in the soul an appetite for such things, and knowing no appetite is made by God

in vain, Lewis concludes that the pursuit of the liberal arts is pleasing to God

and is possibly, for some, a God-given vocation.

Everyone is called by God to do some

work, yet each calling is different for each person, and part of the art of Life

consists in finding and fulfilling this calling. As Lewis writes, "a mole must

dig to the glory of God and a cock must crow." Further, those who pursue a life

of learning perform a valuable service for those who do not. "Good philosophy

must exist," Lewis writes, "if for no other reason, because bad philosophy must

be answered." If those who possess the inclination and leisure for the life of

the mind refuse to enter the arena of ideas--"not to be able to meet the enemies

on their own ground"--then they will place those who have no such inclination

and leisure at the mercy of proponents of bad ideas. In Lewis’s words, "nonsense

draws evil after it." As Lewis concludes, "we can therefore pursue knowledge as

such, in the sure confidence that by so doing we are either advancing to the

vision of God ourselves or indirectly helping others to do so. . . . The

intellectual life is not the only road to God, nor the safest, but we find it to

be a road, and it may be the appointed road for us."

Last year marked the centenary of C. S.

Lewis’s birth. He was a good man and a rigorous thinker, and he has changed the

lives of many through his insightful writings. We are fully justified in

honoring his life. Further, we will honor his legacy by remembering the

indispensable nature of a liberal arts education. Truly, we ignore the liberal

arts only at our peril. Without them we will find ourselves increasingly unable

to preserve a civilized society, to escape from the errors and prejudices of our

day, and to struggle in the arena of ideas to the glory of God.